Asghar Khan, School teacher, Khyber

The years between 2009 and 2014 were among the most horrifying of Asghar Khan's life.

The gentle schoolteacher lives in Khyber, part of Pakistan's mostly Pashtun northwestern tribal belt, a region that used to be overrun by the Tahreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP).

During the TTP's heyday in the region, Khan saw fellow teachers killed, schools destroyed and girls banned from education.

The TTP didn't approve of Western-style education, particularly for girls, and its commanders would leave the decapitated bodies of teachers behind after an attack, a warning to others.

"When I visited my school after four years ... seats were burned, records were gone, and my office looked like burned garbage," recounts Khan, sitting in his crumbling brick house where he runs a makeshift school out of the courtyard.

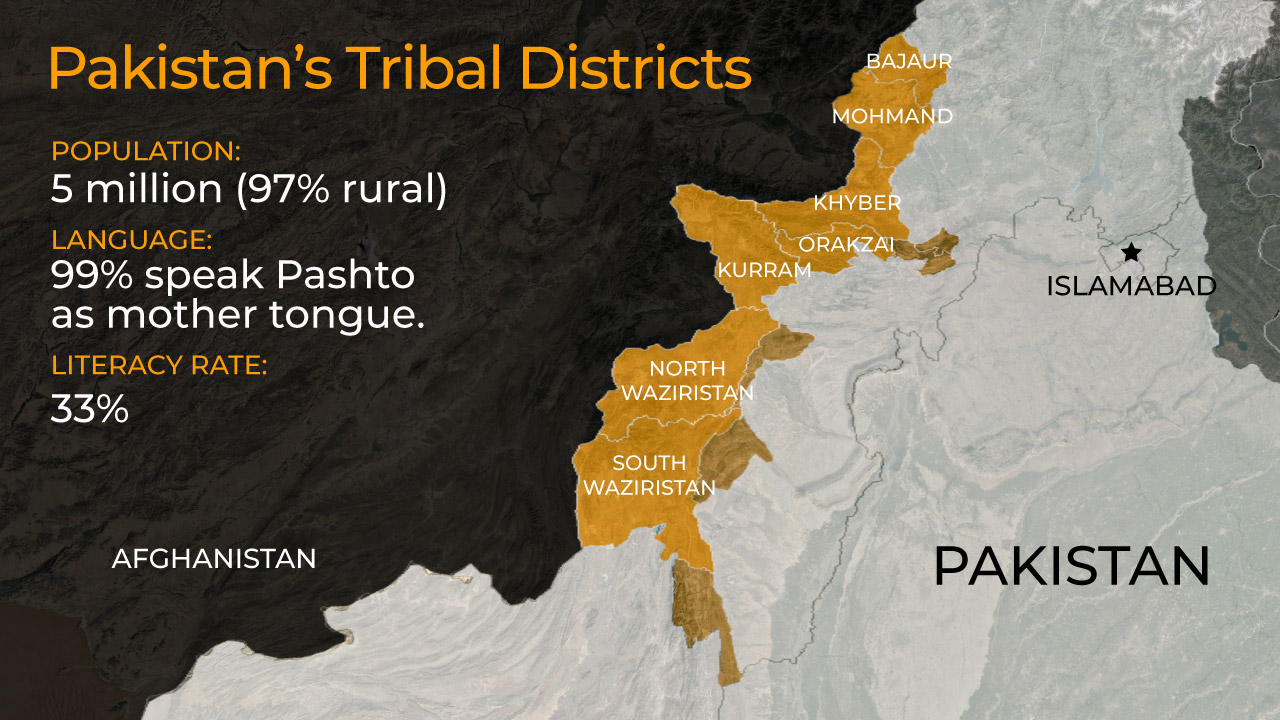

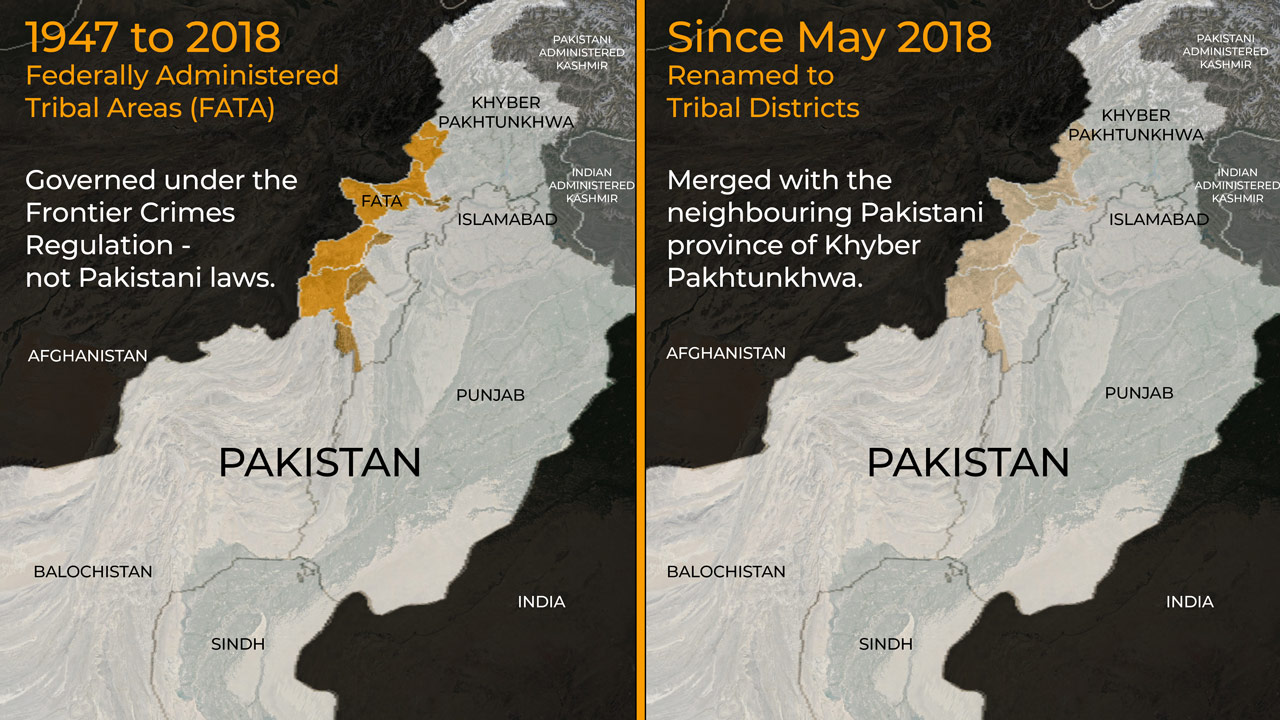

Khyber is one of seven districts previously known as Pakistan's Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), a region on the border with Afghanistan that was governed under the Frontier Crimes Regulation - not Pakistani laws - from 1947 to 2018.

Because Pakistan's laws did not apply in FATA, and national law-enforcement agencies were not able to operate in the region, violence and armed groups were able to thrive for years.

In 2007, Pakistan launched a series of military operations to retake control of the tribal areas from TTP and groups allied to it. Thousands of armed fighters died, as did hundreds of soldiers.

In May 2018, the Pakistani government merged the tribal areas with the neighbouring Pakistani province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, an integration long-awaited by many who were hoping their lives would improve once they became full citizens of Pakistan.

"I haven't seen any change since the merger. The only thing I've seen is fear: fear of the unknown," Khan told Al Jazeera nearly seven months after the government merged Khyber with the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

"We are afraid that we might end up 'finding neither faith nor union with the lover, and belonging neither here nor there'," Khan says, reciting a famous Urdu couplet.

Al Jazeera looks into the situation in former FATA, over a year after it was merged into Pakistan, a process mired in security concerns and bureaucracy that has only resulted in a legal and administrative vacuum.

The merge was meant to empower the millions who lived there but has instead left them uncertain and worried about their future.

The tribal districts cover 27,200sq km along Pakistan's mountainous northwestern border.

A TROUBLED HISTORY

The approach to Khyber is full of signs of the region's volatile past. Low stone structures are scattered around deserted roads that get thicker with army checkpoints and barbed wire blockades the deeper into Khyber it winds.

Since Pakistan gained independence from the British in 1947, FATA - a 27,200sq km belt along the mountainous northwestern border - has been treated differently from the rest of the country.

The Frontier Crimes Regulation (FCR) special administrative framework was set up by the British in the 19th century, giving Pashtun tribes independent control over their territory in order to subdue resistance to British rule.

"The FCR can be seen as an attempt of the British to use Pashtunwali [a non-homogenous tribal code of conduct] to support British state power in an area where they did not think it worthwhile, because of the amount of resistance, to impose British law," says Anatol Lieven, a policy analyst who covered the region as a journalist for years.

"The FCR can be seen as an attempt of the British to use Pashtunwali [a non-homogenous tribal code of conduct] to support British state power in an area where they did not think it worthwhile, because of the amount of resistance, to impose British law," - Anatol Lieven

"The key element ... was to work through local intermediaries, the 'maliks' [tribal chiefs]."

The system rested on the maliks and federally-appointed Political Agents (civil administrators, commonly known as PA's), giving them vast legal, administrative and political powers with little oversight.

It also denied FATA residents the right of legal representation and appeal and enforced a form of "collective justice" by authorising punishment against an entire tribe for alleged crimes by a member.

FCR continued in FATA after Pakistan's independence, the constitution exempting it from parliament's laws and only allowing the president to take decisions about it after consultation with tribal elders. FATA was essentially cut off from fundamental constitutional rights accorded to the rest of Pakistan.

The legal grey area FATA was in was useful for the state: Throughout the 1980s, backed by the United States, Pakistan's then-military government sponsored the formation of the Afghan Taliban as a force to challenge the Soviet Union in neighbouring Afghanistan.

"FATA ... served as a training ground for those who would then undertake strike-and-hide operations in Afghanistan during the Soviet occupation," says Karam Elahi, a scholar on the region.

Kurram, a tribal district blessed with fertile valleys and green mountains.

After the September 11, 2001, attacks, some areas in FATA became even more volatile as al-Qaeda, and subsequently the TTP, found refuge and a foothold there.

According to residents and researchers, these groups gained power through intimidation, bribes, religious propaganda and escalating violence, killing tribal elders who challenged them.

They also destroyed educational institutions and banned NGOs, reversing what scarce development there was in the impoverished area and further isolating FATA's citizens from the rest of Pakistan as governance structures became almost non-existent.

"The entire fabric of society ... everything was terribly affected," says Elahi, explaining how FATA became known as "ilaqa-e-ghair", an area of the unknown, even for Pakistanis living only a few hundred kilometres away.

The entire fabric of society ... everything was terribly affected - Karam Elahi

"Whatever rudimentary form of economic infrastructure and fabric there was, it was also tested and destroyed [by the armed groups and subsequent army operations]."

0 Comments